by Kristin Kirsch Feldkamp, Editorial Assistant

This is the first blog post in a series complementing our current exhibition Still & Art.

Clyfford Still spent his formative years in the West, moving back and forth between the western U.S. and Canada during the first half of the twentieth century. Except for a few brief visits east of the Mississippi, the West was responsible for his education, both formal and informal, and his livelihood as he developed as an artist. And although he spent his mature years living in the eastern U.S., it was the West that was “etched in his psyche”[1] and surfaced time and again in his work.

Still’s childhood began in Grandin, North Dakota, where he was born on November 30, 1904, into a family with a long history of working the land. His paternal ancestors were farmers from Scotland who emigrated to Ontario, Canada in the 1830s. He was the only living child of Canadian immigrants John Elmer Still and Sarah Amelia Johnson Still. Shortly after he was born, in 1905, his family moved to Eastern Washington state near Spokane. Then, in 1911, Still’s father established a homestead in Bow Island, Alberta, Canada and the family moved back and forth between Bow Island and Spokane during most of Still’s youth, as well as, later on, another home in Killam, Alberta. [2]

Life on the homestead farm was tough, and Still described working the farm with gruesome details like being “bloody to the elbows shucking wheat.”[3] At a young age, Still was exposed to the harsher realities of life inherent in nature and he was anxious to escape his family’s legacy of living off the land.

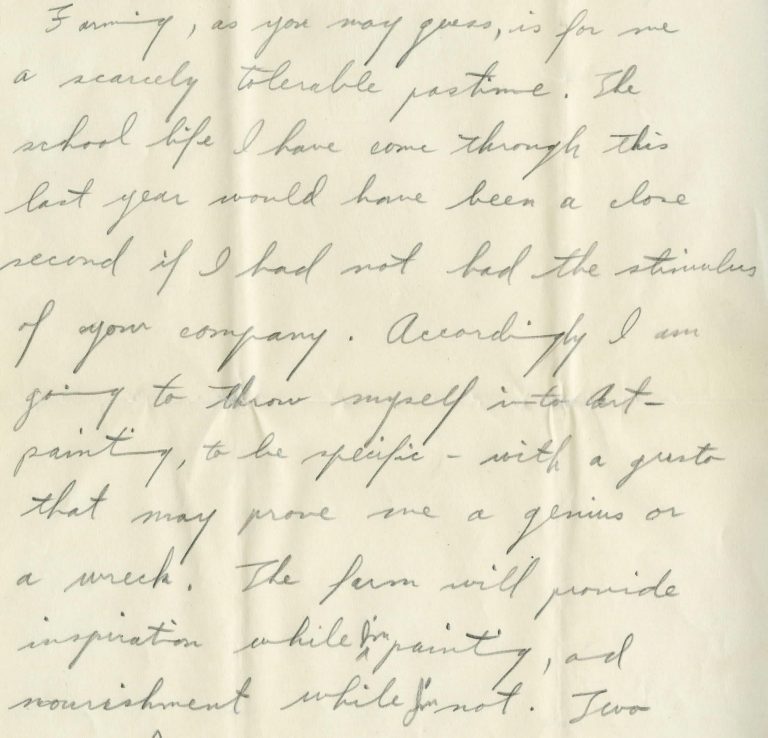

One of the many treasures in the Museum’s archives is a collection of letters Still wrote to friend and Spokane University classmate Weldon Schimke. The letters reveal a young, ambitious Clyfford with a deep longing for more than his current lot in life. In one handwritten letter dated August 13, 1927, Still outlined his escape route: “Farming, as you may guess, is for me a scarcely tolerable pastime. . . Accordingly, I am going to throw myself into Art—painting to be specific—with a gusto that may prove me a genius or a wreck.”

The letters are at turns funny, tender, descriptive, and philosophical; they show a reverence for the power of art and ideas. And they’re a testament to Still’s scruples about the significance of art that were misinterpreted as arrogance often later in his life.

In 1941, with a wife and child, Still moved to San Francisco and found work in the war industry. At a friend’s home in Berkeley, he met Mark Rothko.[4] It was a fortuitous meeting that would trigger Still’s introduction to the who’s who of the New York art scene, Peggy Guggenheim, and eventually the art world at large. A colleague and friend, Rothko wrote the introduction to Clyfford Still’s first exhibition of paintings at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery in 1946. In it he identifies two things about Still that are significant—that he was working alone and in the West.

The West Still grew up in and inhabited was at the same time inspiring and devastating, and the paradox is something you can see in early, realistic works from the 1930s. Still looks back on a youth in which man was pitted against nature in a fierce battle to survive. He grew up in a landscape with snowstorms in which “you either stood up and lived or laid down and died.”

Given Still’s family history and geographical location, it’s remarkable that Still ever chose to become a painter in the first place and in the second place rose to such prominence. But it was Still’s origins in the West that made him extraordinary. According to David Anfam, “The key point is that Still grappled at firsthand with precisely those natural cycles—of the weather and land, involving growth, strife, and dissolution—that since time immemorial have always been grist to the mill of fable.”[4] Still’s rural western experiences gave him a solid advantage that led him to become one of the earliest abstract expressionist painters.

Sources:

[1] David Anfam. “Still’s Journey,” in Clyfford Still: The Artists Museum by Dean Sobel and David Anfam with Forewards by Sandra Still Campbell and Diane Still Knox (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2012), 67. “That Still did at least seven pastels in 1968 evoking the Canadian Landscape alike titled Memory, suggests how these beginnings were etched in his psyche.”

[2] Patricia Failing, “Clyfford Still: An Annotated Biographical Chronology 1904-1941.”

[3] Bailey Harberg, “Happy Father’s Day.” Still Life, Clyfford Still Museum’s Website, June 15, 2012.

[4] Thomas Albright. “A Conversation with Clyfford Still,” ART News magazine, March 1976.

[5] David Anfam, “Still’s Journey” Clyfford Still: The Artists Museum, by Dean Sobel and David Anfam with Forewards by Sandra Still Campbell and Diane Still Knox (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2012), 67.