By Bailey Harberg Placzek, Associate Curator & Catalogue Raisonné Research and Project Manager

The now infamous Sotheby’s shredding stunt Banksy pulled a couple weeks ago may go down as the greatest “thumbing of the nose” statement made to the art market in recent history. Some expressed surprise, outrage, and admonishment over the enigmatic British artist’s outright mockery of the art world and its sometimes confounding inner-workings. Yet here at the Clyfford Still Museum, Banksy’s calculated destruction brings to mind antics typical of our beloved Clyfford.

The recent Sotheby’s act reminds us of one story in particular—when Clyfford Still famously sliced one of his paintings right off the wall of Alfonso Ossorio’s lavish East Hampton home. Ossorio was one of Still’s collectors and a fellow abstract expressionist artist. After months of tense communications with him, Still began to feel that Ossorio did not understand his work as much as he originally thought and asked for the borrowed work to be returned to him. After ignoring Still’s requests and several ensuing arguments, Still took matters into his own hands. He later wrote of the incident in his journal on January 17, 1958:

We arrived in East Hampton, got in a taxi, drove to the house. The taxi was ordered to wait. Pat rang the bell. We waited. Ted opened the door and was effusive with greeting. While he went to get Alfonso, we walked in. Slowly, but deliberately, we made our way to the center of the main room, not sure where the picture might be. … I went down into the studio…the canvas was the one picture hanging that I saw. I walked over to it, felt the corner, tugged on the stapled edge a moment, noted its size, weight, the space it would take if hauled down. I stepped back, looked at it. What should I do with it? There was a step ladder in the center of the room. I paused maybe 15 or 20 seconds. And, as I looked up at it, I knew what I had to do. What I had to do was so clear that I am conscious of every instant. I had to perform a surgical operation. … So, I took out my knife, opened it, carried the step ladder to a spot in front of the picture, mounted it, and with a strong, deliberate hand, cut a huge rectangle out of the center of it, leaving a rim of canvas about a foot in width on the stretcher; one brilliant spot in the lower right-hand corner which leapt out like a flame — this I also cut out in the shape of a small square. These pieces I laid on the floor and folded, face inward, into a flat bundle which I tucked under my arm. I picked up my hat, walked toward the corner stairs. … I went out of the door and got into the taxi, placing the bundle at my feet.

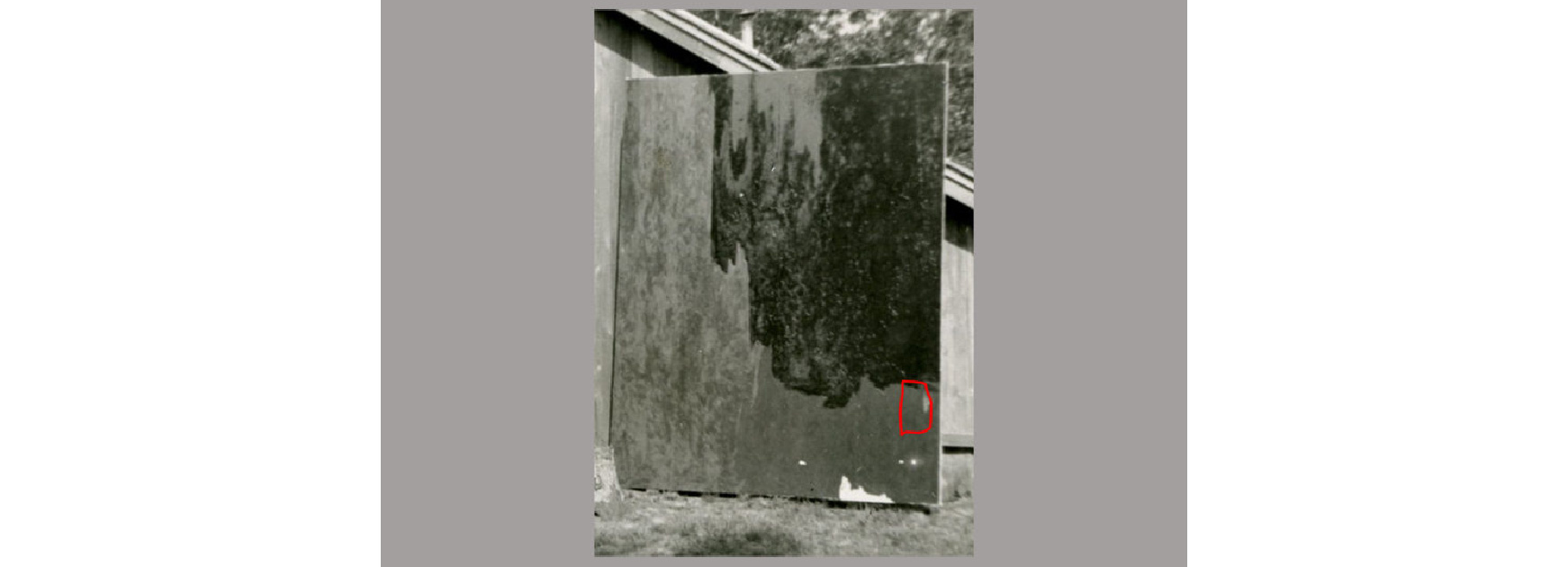

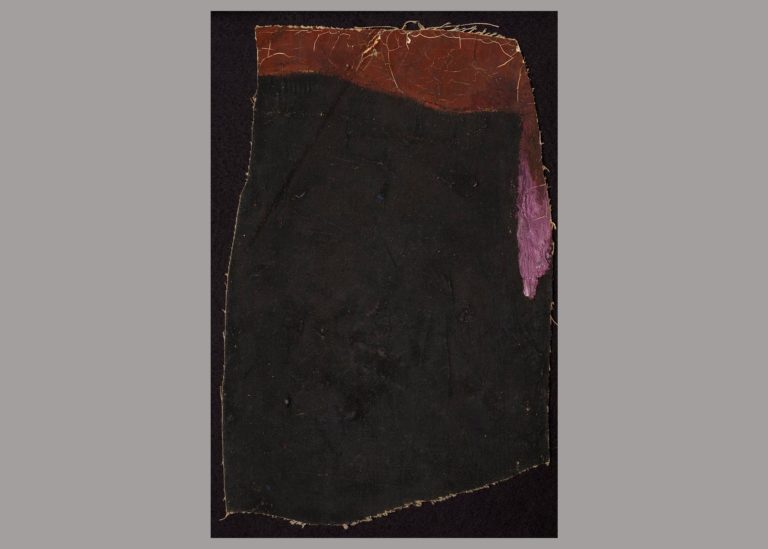

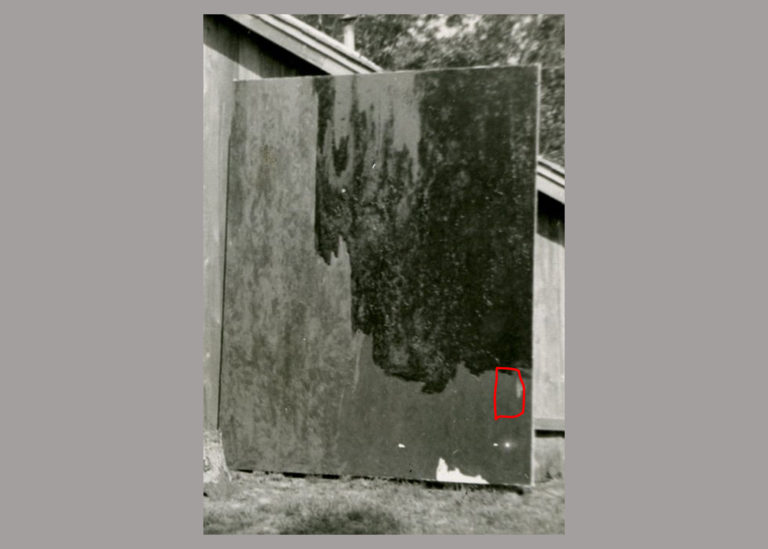

The Stills never documented the destroyed painting in their inventory. Perhaps because the work had “become something else than what [Still] had made it” and “become the wrong kind of force…a symbol” (Clyfford Still journal entry, January 17, 1958). Through researching the story a couple years ago, we found an archival image showing a large, unknown painting leaning up against a barn at Ossorio’s East Hampton house. Unbelievably, an area in the lower right-hand corner of the mysterious painting seemed to match an undocumented, small painting fragment previously found in the collection. Might this fragment be the “one brilliant spot” that “leapt out like a flame,” which Still preserved as a sort of reminder to himself of what the painting had originally been?

Yet, like Banksy’s partially-shredded Girl With Balloon, the Still fragment is not just a relic, an empty casualty of creative forces at work. The “destroyed” objects are both catalysts for our deeper understanding of what art is and is not, and if it can ever truly be borrowed, sold, or owned.