by Jennifer Davey

The National Gallery of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum recently announced a major gift of photographs from the collection of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser. Among the works are photographs by Dorothea Lange, a twentieth-century photographer whose work has striking parallels to Clyfford Still’s depression era paintings of agricultural laborers.

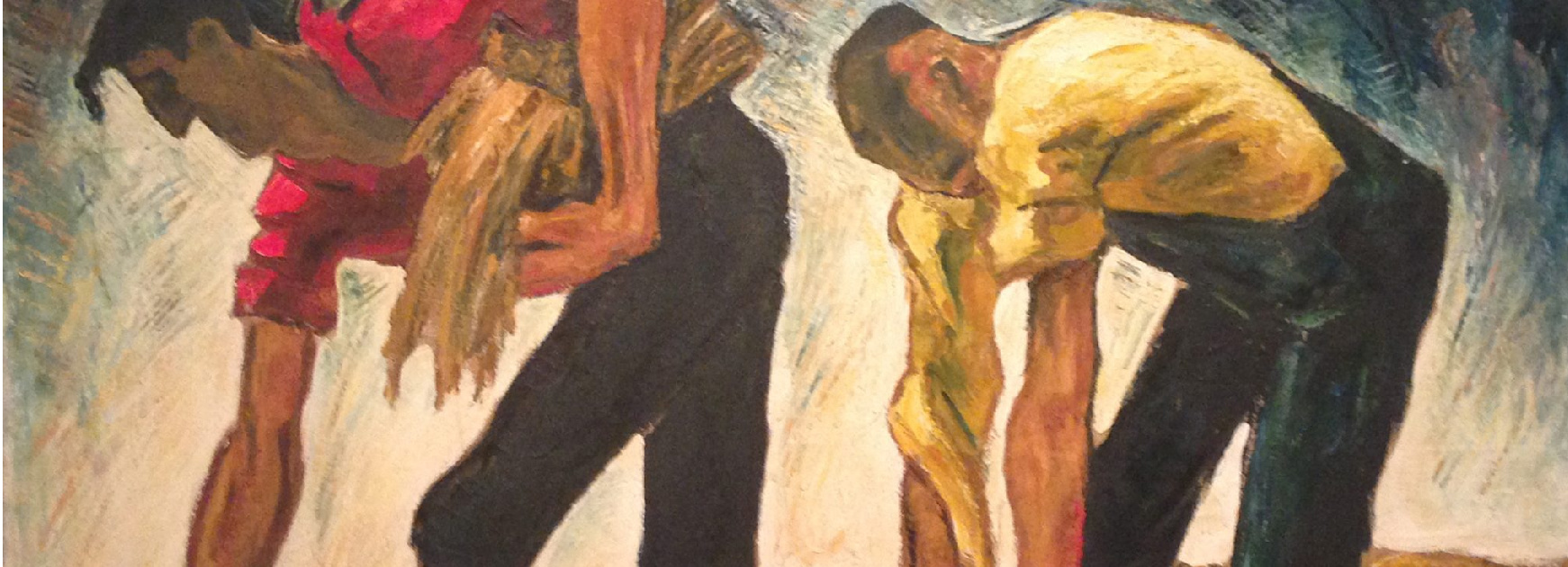

I first noticed the similarities between Lange and Still last year when my husband stopped me as I was heading to the Clyfford Still Museum (where I volunteer). He wanted to share his latest book acquisition. “I think you might be interested in something,” he said and proceeded to open The Bitter Years, 1935-1941: Rural America as Seen by the Photographers of the Farm Security Administration. He pointed to Dorothea Lange’s photo Filipinos Cutting Lettuce. We were struck by how similar the image was to Still’s 1936 painting PH-77.

Curious to find out more about these two images and possible reasons why both artists had chosen such similar visual forms to express their ideas, I embarked on a research journey. Had Lange and Still run across one another’s work or was this a synchronicity? Was there something permeating the era that both artists expressed through this archetype of farm laborers?

Lange took her photo while traveling across the United States during the Great Depression, a period of severe economic hardship that spanned the decade between 1929 and 1939. While reading my husband’s book, and doing further research online, I discovered that the Farm Security Administration (FSA), formed as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, began hiring photographers in 1935 to document the impact of the depression. The FSA hired Lange along with Paul Taylor, and the duo traveled to the most challenged rural areas of America.

Coincidentally, their travels included a stay in Washington’s Yakima Valley, not far from Washington State University (WSU) where Still was a professor. PH-77 was created while he was teaching at WSU, and exhibited in a faculty exhibition in 1938. His background as the child of farmers deeply connected him to both farming life and the hardships experienced by farmers during the Great Depression. In a review of that faculty exhibition, Still explained how “he had the idea for the painting germinating in his head for a year and in two weeks’ time brought the idea to fruition.” It seems therefore that the idea for this painting came to him in 1935, the same year that Lange started her photo project for the FSA.

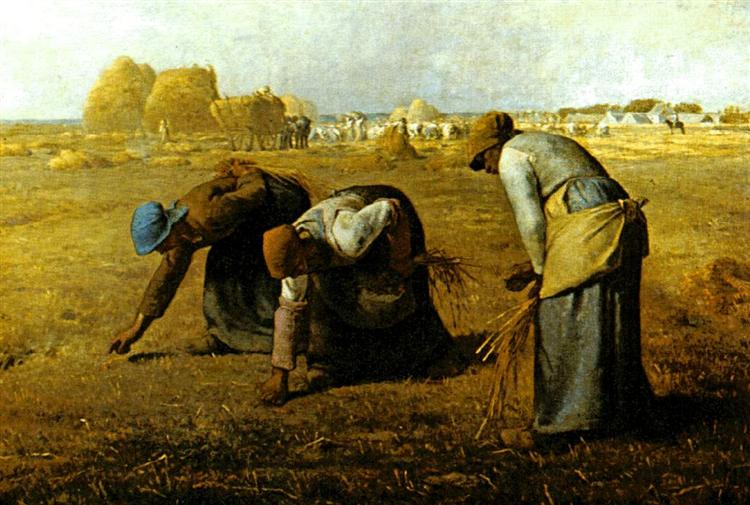

Although Lange was traveling and taking photographs in 1938 and 39 when Still displayed PH-77 at WSU, I could find no evidence to suggest that Lange may have seen this painting. Interestingly, it may be art history that links the two images together. Jean Francois Millet painted The Gleaners in 1857. At the time, Millet was criticized for focusing on the so-called menial subject matter of farm laborers. However, Millet was determined to paint direct experiences from his life as a peasant farmer. Still and Lange not only mirror the formal aspects of The Gleaners; like Millet, they chose to portray real, human experiences from their time. In the 1930s, this was still a new idea in art.

When comparing the Lange and Still images side by side, I am struck by the low vantage point. It elongates the arms and legs of the figures, creating a dramatic simplification of form. It also highlights the negative and positive spaces, flattening the picture plane. To me, simplifying the figures in this way heightens the emotion of the laborers’ struggle. As well, both images emphasize the relationship between the land and people.

Still and Lange shared similar visual structures within their work, but I was surprised also to find quotes that linked their shared belief in highlighting the un-beautiful. Lange states: “Sometimes in a hostile situation you stick around because hostility itself is important.” Still writes: “There were unbeautiful things in life worthy of expression upon canvas.” In these quotes, you can see both Still and Lange edging towards modernism. They both sought to capture this challenging time in American history by highlighting the emotional truth.

I left my home that morning with my husband’s new book in hand, and when I got to the Museum I was excited to see that PH-77 was on view. I could examine the painting in person along with the photograph in the book. Although Lange and Still probably never met, this chance meeting of images allowed me to explore some interesting commonalities between the artists. It also enabled me to learn more about an era that defined an artistic moment for both Lange and Still.

[Editor’s note: After some time in storage during the last two exhibitions, PH-77 goes back on view April 9–September 24 at CSM.]

Sources:

- Washington State University school newspaper, 1938/39 (in PH-77 file@Clyfford Still Museum)

- Anne Whiston Spirn, Daring to Look, Dorothea Lange’s Photographs and Reports from the Field (University of Chicago Press, 2008). www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/769844.html

- The Art Story Contributors, Dorothea Lange, (The Art Story, 2016). http://www.theartstory.org/artist-lange-dorothea.htm

- The Biography.com Editors, Dorothea Lange Biography, (A&E Television Networks). http://www.biography.com/people/dorothea-lange-9372993

- Edward Steichen, The Bitter Years 1935-1941 Rural America as seen by the photographers of the Farm Security Administration (Museum of Modern Art, 1962)

- Stephanie Whitney, Part Two: Dorothea Lange in the Yakima Valley, Rural Poverty and Photography in the Depression (Washington State University, 2010). http://depts.washington.edu/depress/dorothea_lange_FSA_yakima.shtml

- Musee de Orsay, The Gleaners. http://www.musee-orsay.fr/index.php?id=851&L=1&tx_commentaire_pi1%5BshowUid%5D=341

- The Gleaners: Jean Francios Millet: Analysis Visual Arts Encyclopedia. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/paintings-analysis/gleaners-millet.htm