By Jennifer Davey, CSM Volunteer

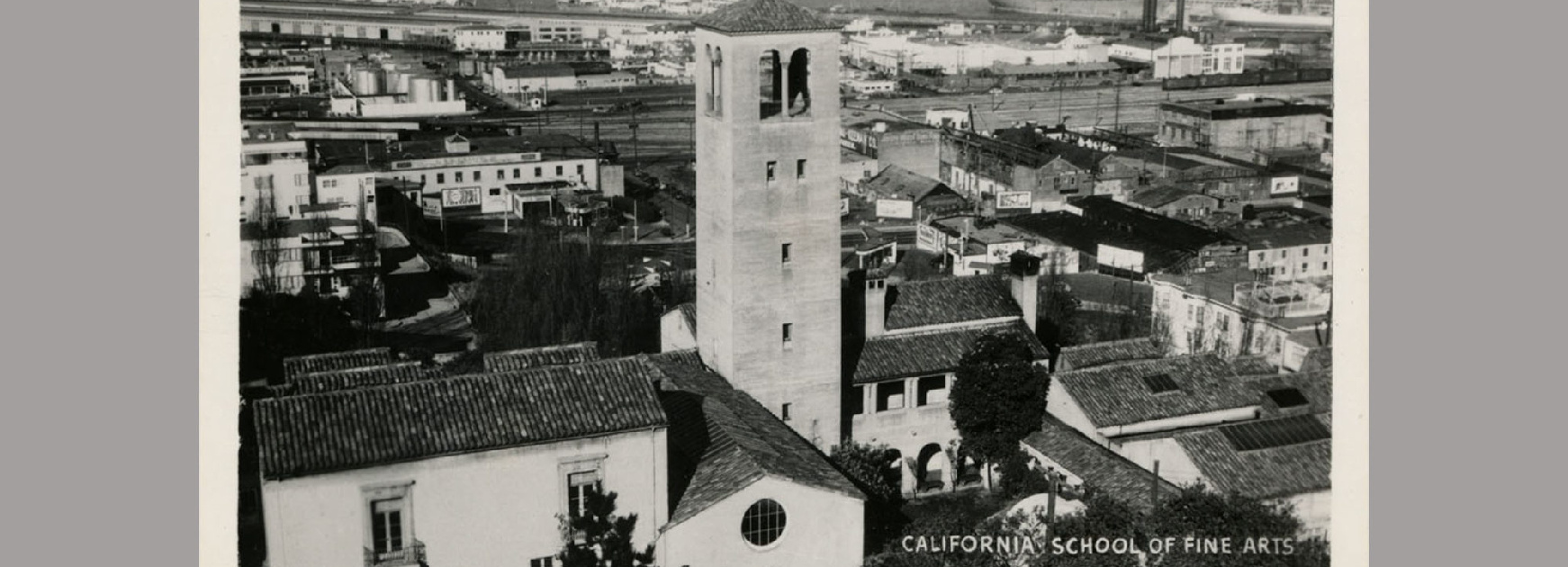

In 1945, the California School of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute) hired Douglas MacAgy and gave him free rein to revise curriculum and hire faculty as he saw fit in a push to modernize the school. So, MacAgy gathered a faculty based on the principle of “vision over craft, and spirit over method”[1]; he hired a range of dynamic teachers, many of whom went on to become legends in their fields. Two of those teachers were Clyfford Still and Minor White. At California School of Fine Arts (CFSA), Still and White created a new way of seeing in both painting and photography.

MacAgy hired Still in 1946 to lead the painting department, along with Hassel Smith, Dorr Bothwell, Claire Falkenstein, David Park, Clay Spohn, Elmer Bischoff, Ed Corbett, and Richard Diebenkorn. MacCagy also invited New York artists Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt to teach summer sessions, thereby making the school a hub for the art movement that would become known as Abstract Expressionism, as well as connecting Still to New York City.

MacCagy hired Ansel Adams in 1945 to create the first fine art photography program in the United States. Under Adams’s leadership, the program strove to teach the expressive and creative possibilities of photography. To that end, Adams contacted Minor White, who was living in New York City, to offer him a teaching position. Inspired by the West and the possibilities of teaching, White moved to San Francisco and became a key leader among the photography faculty at CSFA. His colleagues included Dorothea Lange, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, and Lisette Model.

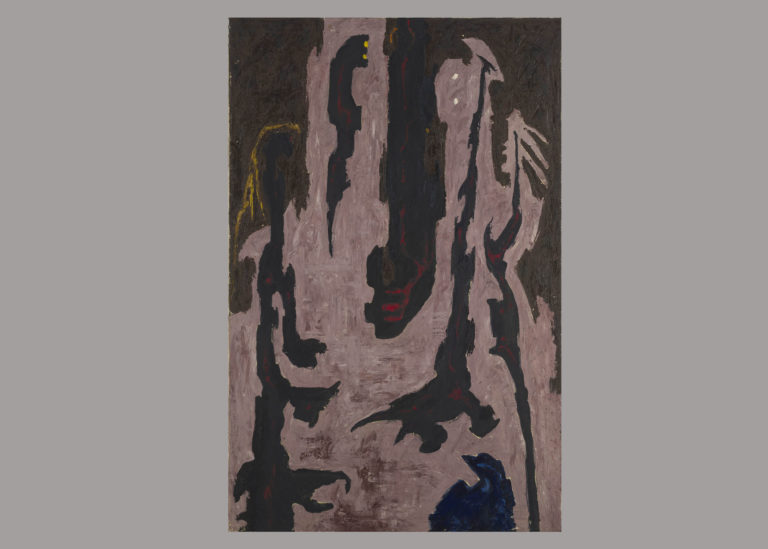

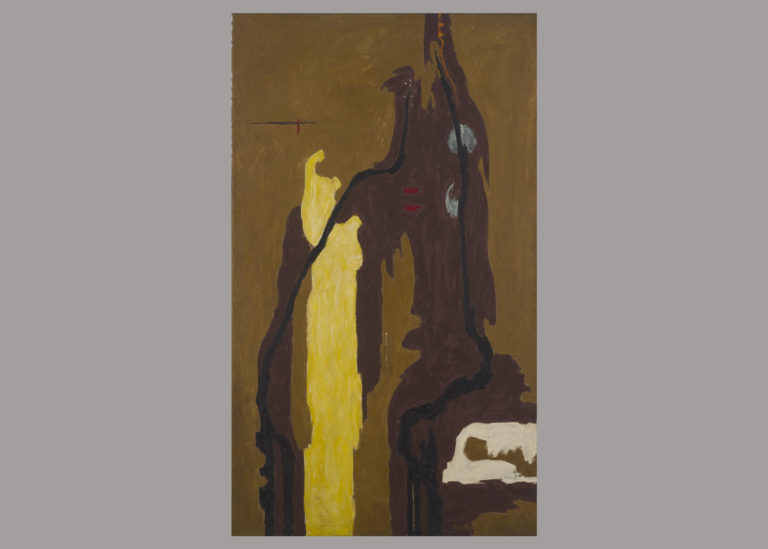

At CFSA, Clyfford Still and Minor White transformed the way visual language was used. They peeled away layers of perception and pointed the viewer inward. Still did this by breaking apart the human form, leaving only a symphony of color, jagged shapes, and often bare canvas to reveal an underlying spirit. “Paintings by Clyfford Still” (July 2 – August 3, 1947), Still’s solo exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, strongly impacted many artists working in the Bay area at the time.[2]

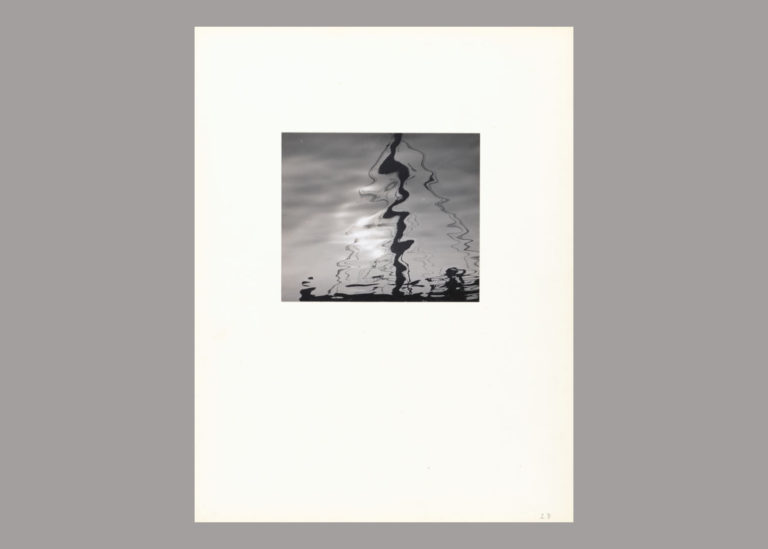

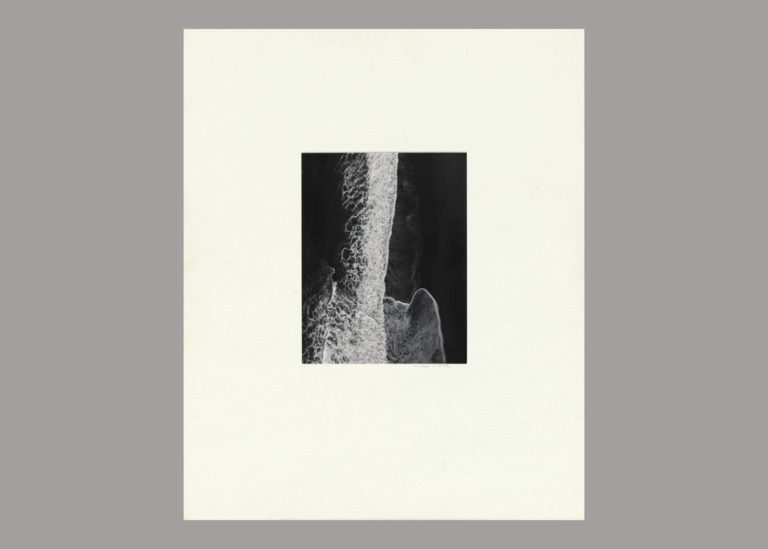

White, inspired by Alfred Stieglitz’s idea of equivalence, used both realistic and abstract photography to express inner states of being. According to White: “If the individual viewer realizes that for him what he sees in a picture corresponds to something within himself—that is, the photograph mirrors something in himself—then his experience is some degree of Equivalence.”[3]

Although it is not clear how much Still and White interacted at CSFA, it is interesting to see the visual links between Still’s paintings from the Legion of Honor exhibition and White’s abstract photographs from 1947. That said, it’s probable Still was aware of the photographic work Minor and his colleagues were doing and vice versa. Certainly, the CSFA proved to be an epicenter of creative activity in which artists of the time forged new paths of expression, both in paint and photography.

Sources:

[1] Comer, Stephanie, et al. The Moment of Seeing: Minor White at the California School of Fine Arts. Chronicle Books, 2006.

[2] www.clyffordstillmuseum.org/archives

[3] Minor White, Equivalence: The Perennial Trend, PSA Journal, Vol. 29, No. 7, pp. 17-21, 1963.