By Bailey Harberg – Collections Manager

It’s a familiar feeling for many of us.

You walk into an art museum excited about the one-of-a-kind, over-the-top inspiring moments you are about to experience.

Then it happens.

You come face-to-face with an all-white painting.

Your first thought is, “What am I supposed to do with this?”

So what are we supposed do with all these white paintings?

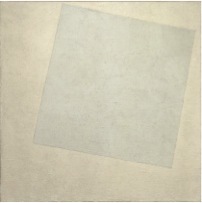

The idea of a white painting, as we know it can be traced to Russian Suprematist Kazimir Malevich when he painted White on White in 1918. His theory was that painting should create within its viewers a “pure feeling,” which could be achieved through stripping art down to its essence.

Inspired by Malevich, Constructivist artist and photographer Alexandr Rodchenko decided that he should paint some of his own monochrome paintings, but with a very different goal in mind. In 1921, Rodchenko created and exhibited three monochrome paintings—one red, one yellow, and one blue—as a proclamation of painting’s death and the end of bourgeois art tradition.

However, unfortunately for Mr. Rodchenko, painting wasn’t going anywhere. In fact, his take on Malevich’s white monochrome paintings actually sparked quite the scandal several decades later in the U.S. when Robert Rauschenberg decided to tackle the idea of monochrome painting from what is thought to be the first post-modern American take on white paintings.

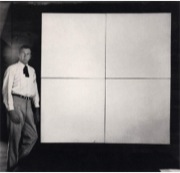

In a blatant statement against the popular Abstract Expressionist movement dominating the NYC art scene at the time, Rauschenberg exhibited his 1951 White Paintings at Stable Gallery in 1953. Critics announced that Rauschenberg’s white paintings were a “gratuitously destructive act”; a plain white canvas was the farthest you could get from the Abstract Expressionist notion of the unique individual. Soon after that, Rauschenberg took it a step farther with his famous Erased de Kooning Drawing, which literally obliterated Abstract Expressionist ideals (come check out the CSM interactive timeline for a great video interview with Rauschenberg about this one).

After Rauschenberg, the white painting trend continued with artists such as Ad Reinhart, Agnes Martin, and Robert Ryman, who still creates white paintings today. Even though artists use the “white painting” for different objectives, the play of light and shadow, using the canvas to inspire a unique meditational experience absent of all outside references, and the inevitable comparison with notions of the “white-cube” gallery all play into the layers of meaning hidden under all that white paint. In my opinion, the best part about white paintings is that we can do whatever we want with them.

Here’s the kicker.

We found a white Clyfford Still painting the other day.

Painted in 1949.

Two years before Rauschenberg’s white paintings.

WHAT?!

Images (Top of page; from top):

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: 1. White on White, 1918. Oil on canvas, 31 ¼ x 31 ¼ in. Museum of Modern Art, New York. 2. Robert Rauschenberg with White Painting (four panels), 1951, house paint on canvas, 72 x 72 in. Collection of the artist’s estate. 3. Robert Rauschenberg, White Painting (seven panels), 1951. Oil on canvas, 72 x 125 in. Collection of the artist’s estate. 4. Robert Ryman, Untitled, 1958. Enamel on linen, 10 ⅛ x 10 ⅛ in. Collection SFMOMA.

(Bottom): Clyfford Still, PH-1180, 1949. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 X 62 1/2 in. © Clyfford Still Estate.