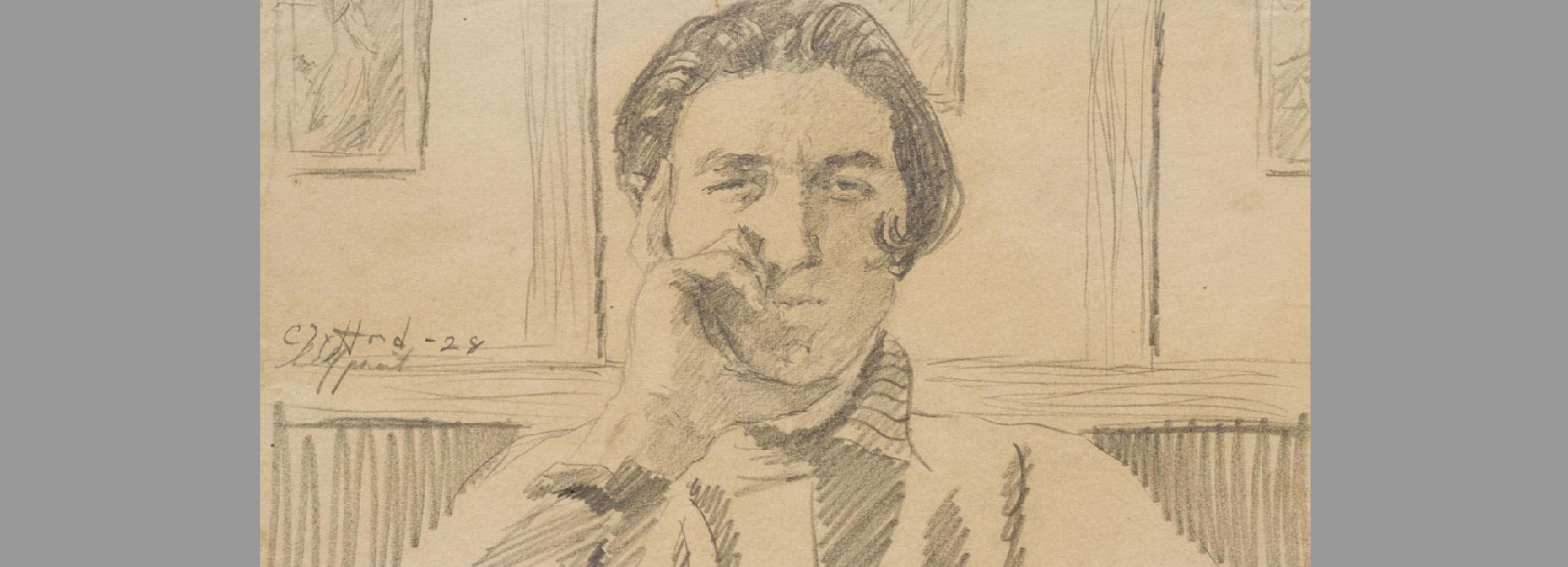

Less is known about Still by the public than many of his contemporaries—like Jackson Pollock—who have been the subjects of movies, books, and lore. So, on what would be Clyfford Still’s 113th birthday, we’re dispelling four common myths about Still.

Myth: Clyfford Still, one of the early Abstract Expressionists and part of the New York School, was a New Yorker.

Reality: Still in fact spent his formative years in the West and his work was heavily influenced by the Western landscape and his upbringing there; his family moved back and forth between Spokane, Washington and a homestead farm in Alberta, Canada. After graduating from Washington State College (now Washington State University) with a master’s degree, Still remained as a member of the faculty. During World War II Still moved to the San Francisco Bay area to work in the war industry and, after a brief stint in New York, joined the faculty of California School of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute). In 1950, at the age of 44, Still moved to New York for eleven years. He left New York in favor of rural Maryland where he stayed for the remainder of his life.

Myth: Clyfford Still was at war with the art world.

Reality: According to our associate archivist, Farrah Taylor, after reading through his diary notes and correspondence it becomes clear that the truth is more nuanced. “He had high standards and hopes, and he did not feel the need to mess around with things that fell short. He was extremely smart, and he was on a mission,” she said. In an interview with J. Benjamin Townsend, Still said, “I do not hate the public. I like people.” Townsend goes on to explain that like “a modern Coriolanus, he would rather risk public attack or a ‘black-out’ than allow himself to be promoted by huckstering or any demagogic means.” [1] Still had a unique vision and he was unwilling to compromise it for money or recognition.

Myth: Clyfford Still was an action painter.

Reality: Unlike fellow Abstract Expressionists Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, Still was not an action painter. The term action painting was coined by critic Harold Rosenberg in a groundbreaking 1952 article entitled “The American Action Painters“ [2] that described a style of painting in which the physical act of painting was central to the work and the painting was not preplanned. In the Townsend interview, when asked about action painting, Still said, “I am not an action painter. Each painting is an act. The result of action and the fulfillment of action…No painting stops with itself, is complete of itself. It is a continuation of previous paintings and is renewed in successive ones.” [3] When you consider the duplicate paintings with slight variations Still created, many highlighted in our 2015 exhibition Repeat/Recreate, it’s clear that Still’s process was premeditated and painstakingly thought-out.

Myth: Clyfford Still was a brooding, solitary, unpleasant fellow.

Reality: The so-called New York School was a rowdy bunch, known for heavy drinking and wild antics, and it has been rumored that Still could drink Jackson Pollock under the table when he wanted. We have a great deal of correspondence in the Clyfford Still Archives that suggest Still was outgoing and had many great friendships. He was a loving father, husband, and had interests besides art—music, cars, and baseball chief among them. In the Clyfford Still Archives, which now has many photos and documents viewable online, there are countless pictures of Still with his daughters, second-wife Patricia, and friends, including Douglas MacAgy and Mark Rothko. Although deeply principled with strong convictions, Still was not antisocial or unfriendly.

In keeping with our mission to reveal Clyfford Still and his works to the public, the Museum recently made over 2,200 works by Still available online as well as countless archival documents.

Sources:

[1] Townsend, J. Benjamin. Gallery Notes, Allbright-Knox Art Gallery, Vol. 24 summer 1961 pp. 9-14.

[2] MacAdam, Barbara A. ArtNEWS, “Not a Picture but an Event.” November 1, 2007.

[3] Townsend, J. Benjamin. Gallery Notes, Allbright-Knox Art Gallery, Vol. 24 summer 1961 pp. 9-14.