By Tim Svenonius, Media Producer, SFMOMA

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is one of very few museums that owns works by Clyfford Still. One gallery in the museum is permanently dedicated to showing a selection of these works. SFMOMA Media Producer Tim Svenonius wrote this reflection on one painting from the collection, PH-58, 1951, just before the museum closed its doors for an ambitious expansion. SFMOMA will reopen in early 2016.

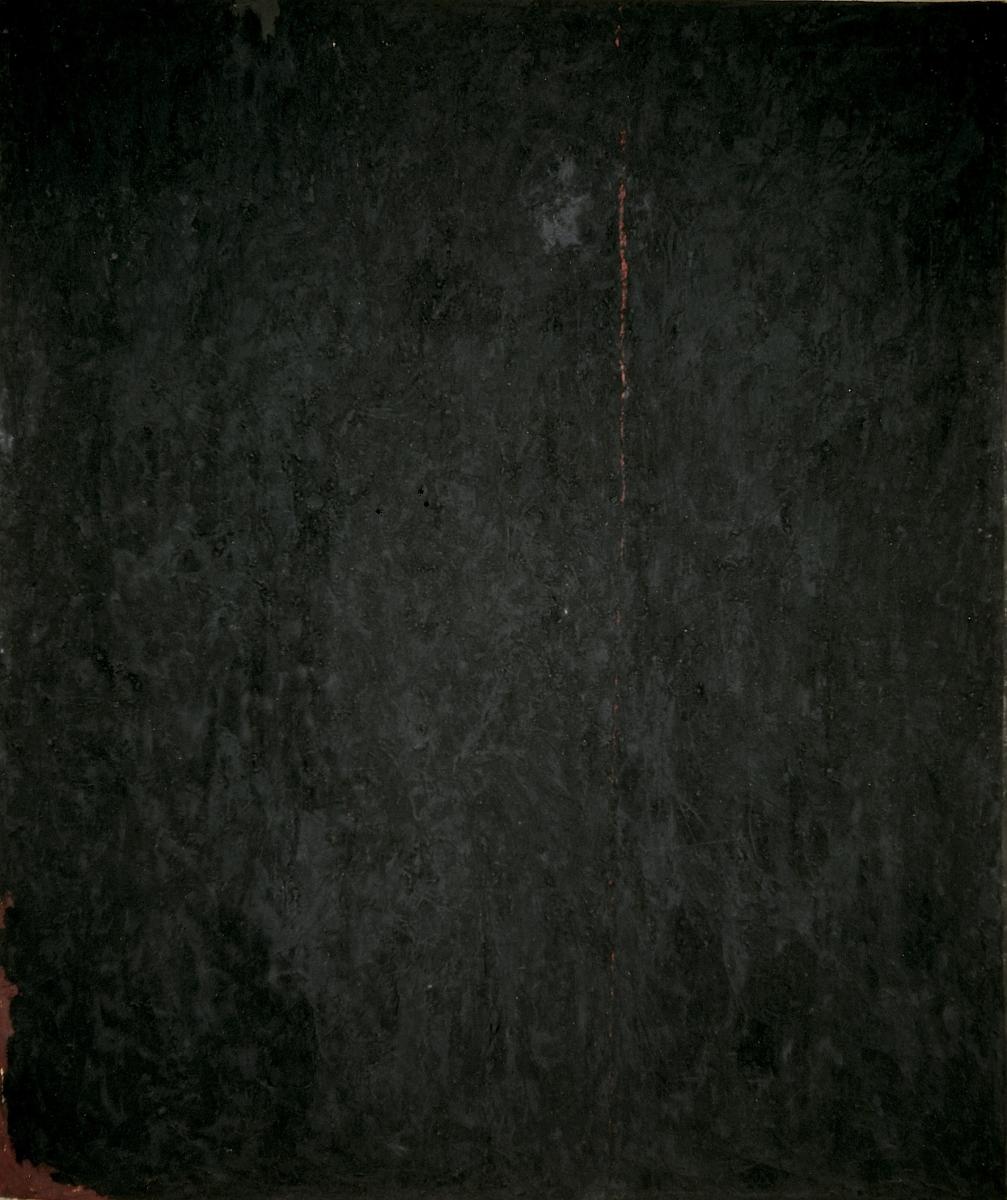

Many times I’ve paused in front of this painting, allowing my thoughts to wander across the rough landscapes of its surface. Austere and silent, it drinks the light from the room like a dark sponge. Though possessing neither the scale nor the dynamism of the other canvases that fill the room, it is this one–the one I’ll call the black painting–that always asserts itself most powerfully to me.

If you are drawn to it, as I have been, it reveals itself as you move nearer. Only then does its volcanic-rock texture come into focus. Or, it may seem not so much mineral as mammalian: woolly like the hide of a huge dark animal. It catches the ambient light gently but resolutely, becoming a field of subtle shadows. Near the top, a break appears in the black expanse–a vivid red cut in the dense surface. Below, a patch of deep crimson covers a bottom corner. Yet in essence it is monochromatic, and motionless. This work will engage those who choose to confront it but will remain opaque to any who saunter past with only a glance.

Still once wrote of his work, “These are not paintings in the traditional sense; they are life and death merging in fearful union.”

His remark is at once revealing and cryptic. A fearful union of life and death has mystical overtones, and to assert that his artworks are that union, speaks to a religious-like reverence he held for his paintings and his process. With his statement in mind, I began to look at each of his paintings as part of a mythical cosmogony, each one a collision of powerful opposites.

In science as well as myth, the creative and destructive forces that shape our world are considered to be inseparable. In both ways of telling the story of our universe, it is through catastrophic or violent change that the world around us is renewed.

In the beginning, we are told, in religion as well as science, the world was formless and void, and darkness was on the face of the deep. On this point nearly all accounts of the beginning seem to agree: a shared notion of nothingness and darkness. As to what happens next, of course, there is considerable disagreement.

The beginning as told in Genesis seems to occur with quickness and ease: Let there be light, and there was light. But many other creation stories are filled with clashes and conflicts, revolutions and patricide. In most traditions gods are overthrown to make way for new generations; sometimes the deposed gods are dismembered for the good of future generations. In the Babylonian myth, humankind is made from the flesh and bones of a slain war god; in the Norse creation myth, when the giant Ymir is slain, his body becomes the land and his blood becomes the sea.

Not quite a century ago, astronomers decided that all the matter in the universe had once been contained in a single point in space–one impossibly dense speck of matter. This point was so volatile that the only thing it could possibly do was to explode into a vast confusion of energy. Then, over thousands of years, this swirling, churning chaos formed into galaxies and stars, and thus our universe was born.

The “big bang,” with its abrupt beginning and slow unfolding, contains echoes of creation mythology: a sense that the formation of the world is still happening all around us. For the ancients, all of civilization was part of a divinely-sanctioned battle against chaos. In the Islamic faith it is understood that every newborn child or budding flower is a part of the ongoing creation of the universe.

In many of Still’s canvases I imagine I’m seeing a piece of something much larger–as though the subject is of staggering scale, extending indefinitely in all directions, of which we only see an detail—and even that detail towers over us. The black painting, meanwhile, is not just part of a whole. It is the whole: it seems somehow all encompassing, limitless in its density, as though within its boundaries it could contain enough matter to create a universe.

Standing amid the roomful of Still’s metamorphic images, I could see turbulent, cataclysmic events unfolding, each one yielding something new and unknown–geological, cosmological, spiritual. But as I turn back to the black painting, I see the time before time, before words, before all that we know: the profound, pregnant emptiness.