By Kristin Kirsch Feldkamp

“Well, it’s been told over and over again, but it seems that the writers and the people who tell it never get it quite right,” Sandra Still Campbell, Still’s younger daughter, said, in a 2017 interview with our associate archivist Farrah Taylor Cundiff. Sandra was referring to “The Well Story” as it’s commonly known here at the Clyfford Still Museum. It’s a dark tale, befitting the macabre mood of October, that reveals an aha moment in Still’s development as an artist. As Halloween approaches, it seems like the right time to share this spooky story and set the record straight once and for all.

Our story begins in the early 1900s at the Still family farm in Alberta, Canada. The cast of characters includes a young Clyfford, his father, Elmer, and a professional whom Elmer has hired to dynamite their clogged water well in order to free it up. The excerpt below which recounts the story is from Chapter One: Life on the West Coast in our podcast A Daughter’s Voice.

[Sandra Still Campbell]

Elmer had hired a professional to come in and open up the well. It was just dirt pretty far down. And it clogged up and he needed to bring a professional in and literally dynamite down to the water. And what happened is, the dynamite did not go off. And the guy wouldn’t go down and relight the dynamite. So in frustration, I guess, Elmer went in to the house and found his son tinkling on the piano. And he challenged him! I know that he wanted him to go down and do it, but Dad said it was a challenge. So he did.

It was a very primitive well, it was nothing but ropes and pulleys. It just had shingles around the edges. Very primitive. He was hitched to the rope and they lowered him down— I don’t know— forty or some feet. But it was to the point where it was hard to light a match. Very little oxygen down there. Very damp. Very dark. It must have been terribly horrifying! Well he got it lit and they pulled him up, and then Elmer and the professional patted him on the back, like “Oh brave boy.” Dad just stood back and looked at them. He just waved them off. He walked away and just waved them off, “Don’t wanna hear this.”That was the ultimate moment of “I don’t matter to Elmer.”

The only child, the only son, and he was expendable for a well that he didn’t have the courage to go down himself, which is what he should have done. I think contempt for his father came at the moment. The light-bulb moment of “Oh my god.” He always said, “I’m just free labor.”

It’s worth listening to this story as told by Sandra; in addition to being a masterful storyteller, she’s one of the few people living today who had an intimate relationship with her father. The story, according to Sandra, is less about trauma—something other renditions in The New York Times and elsewhere would have us believe—than a freeing realization. It was a “light-bulb moment” Still had about his lack of value to his father which set him free to pursue a career as an artist.

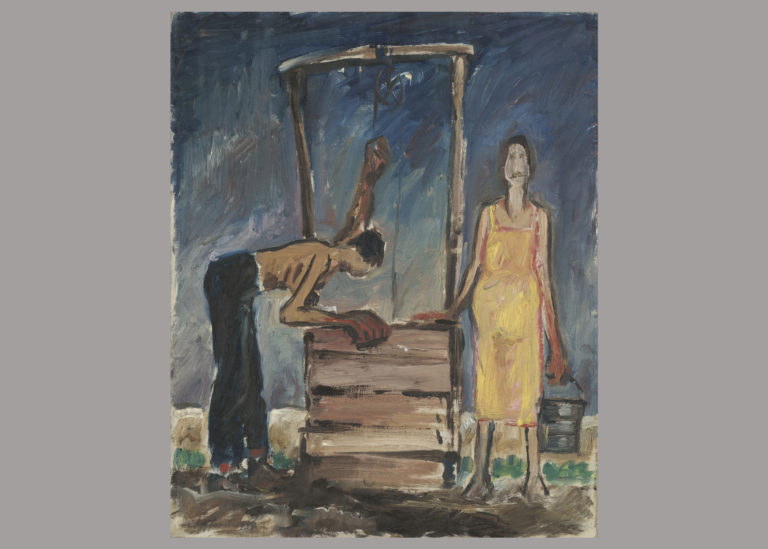

Still would come back to this “light-bulb moment” more than once. In 1934, his first summer at the prestigious Yaddo artist’s retreat, a summer that launched him on a path toward abstraction, Still made a small painting of a ghostly, emaciated, shirtless man bending over a well, looking for or at something (it’s not clear). Next to him, a woman in a simple yellow dress holds a bucket and stares at the viewer, her mouth agape. The painting seems like a clear nod to Sandra’s version of the story. It was a story, according to Sandra, that Clyfford “told a lot to us [his family], because he did not like his father.”

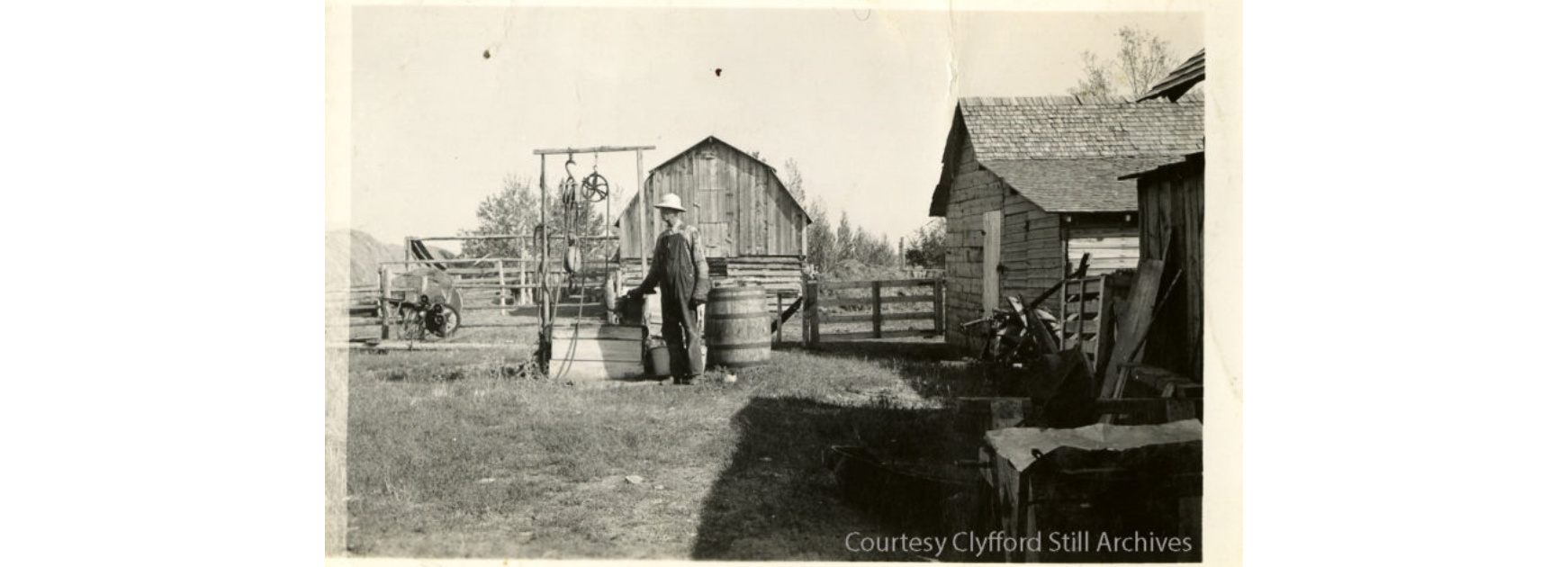

In 1940, Still took a photo of Elmer in front of the well on the family’s farm in Alberta. Elmer wears a hat, heavy work gloves, and overalls. He balances a bucket against the edge of the well with his right hand. The well is small and primitive looking, encased in shingles, with a mechanism for retrieving water that looks like a series of rickety pulleys. It’s hard to imagine sending anyone down into the well to reignite dynamite, let alone one’s child.

“I want the story told,” Sandra said in the 2017 interview, and now we have told it. And if fear of the unknown is the basis for a good spooky story, The Well Story has it in spades. We can only wonder what it must have been like for a young Clyfford to climb over the edge of the ramshackle family well, not knowing if the dynamite was indeed unlit or still lit but delayed in exploding. We can only imagine what he saw or felt when he was forty feet underground struggling to light a match. He left us clues–his painting, a photograph, the oral history of the story–but in the end, as with his paintings, the interpretation is up to us.