This is the third in a series of posts complementing our current exhibition, Still & Art. Read the first post and read the second post.

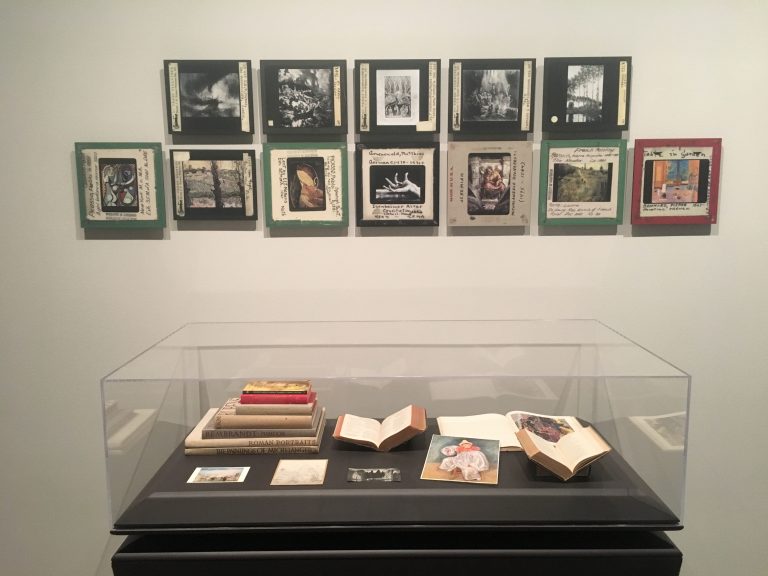

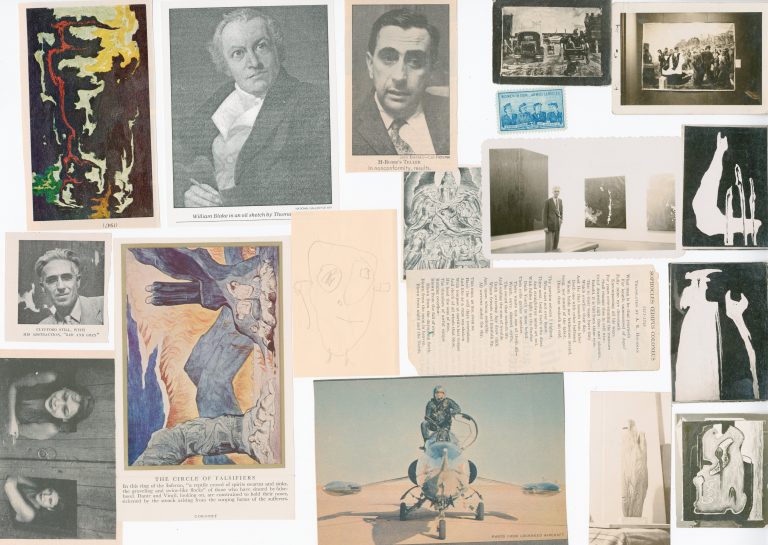

In our final week of Still & Art—an exhibition occupying all nine galleries of the Museum, which channels Clyfford Still’s vast knowledge of art history and explores the idea of artistic influence—it seems fitting to end with a post on Still and William Blake. According to Jessie de la Cruz, our Archivist and Digital Collections Manager, William Blake appears more than any other artist, musician, or writer in the Clyfford Still Archives.

We asked Dr. David Anfam, curator of Still & Art and Director of the Clyfford Still Museum Research Center, what his thoughts were on Still and Blake. “Clyfford’s personality was too strong to be impacted outright by anyone,” he notes. “Nevertheless, he held Blake in the highest regard. Blake was a contrarian who went against the grain of what he regarded as the Establishment and mainstream culture of his times. So did Clyfford. Also, Blake was a ‘gnostic’ — that is, someone who believed that truth had to be inward, not just learnt from others but gained personally. In short, Blake and Still were spiritual soulmates.”

Still’s fondness for Blake has been cited in various sources spanning decades. In a 2001 New York Times article, John Russell describes a youngish Still as a “gifted teacher” who quoted Blake’s “The Tyger” in his classes, loved baseball, and drove a Jaguar around San Francisco. It’s a smashing image and perhaps one that is often overshadowed by reports of Still’s prickly persona later in life.

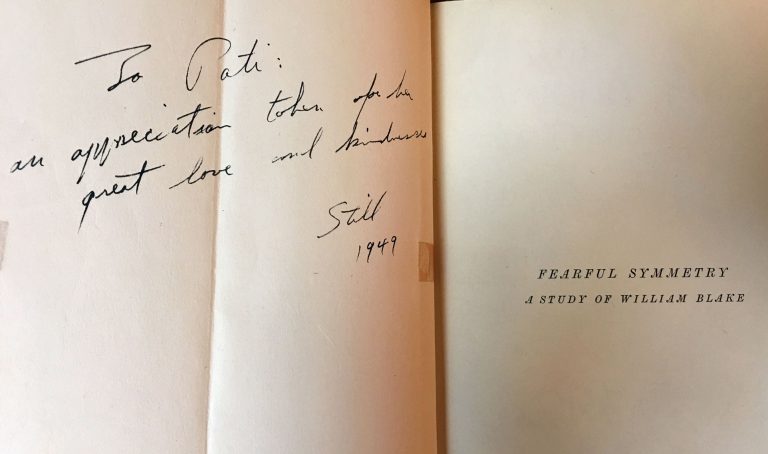

While Still may have quoted “The Tyger” in his classes when he taught at California College of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute) under Douglas MacAgy, there were other works by Blake that resonated with him more deeply. According to Dr. Anfam, “actually there were probably two. The first was Blake’s ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ in which the extremes that Still explored—the abyss and transcendence—come together. I suspect the second was ‘The Everlasting Gospel’. Still quoted it in the catalog to his 1959 show at the Albright-Knox in Buffalo. There, Blake’s words evoke the power of imagination to free the mind ruthlessly from conventional beliefs in order to find radically new ones.”

Still clearly felt an affinity with Blake and the two shared a drive toward transcendence in their work. But something else about Blake might have appealed to Still. Although Blake is widely recognized today—making the BBC’s list of the 100 Greatest Britons of all time in 2002—he was not well known during his lifetime. It’s entirely possible that Blake’s lack of recognition when he was alive appealed to Still.

The Block Museum at Northwestern University’s current exhibition “William Blake and the Age of Aquarius” posits Blake as a “model of non-conformity, self-expression and social and political resistance” during the 1940s and 1950s. Blake essentially became an artistic icon for the counterculture, and this could have made him especially appealing to Still. The curators of the Block exhibition seem to think so because they’ve included an early section which focuses on artists, including Still, working in the 1940s “who discovered Blake’s unique voice in such poems as ‘The Tyger’ and the ‘Shepard’.”

While it’s not possible to say that Blake directly impacted Still’s work, it’s more than reasonable to assume that Still felt deeply connected to Blake. There’s a great deal of evidence to suggest this from archival objects to expert research. It doesn’t hurt that the thought of Blake and Still as spiritual soulmates—transcending boundaries of art and time—is quite inspiring.