by Kristin Kirsch Feldkamp, Editorial Assistant

This is the second in a series of posts complementing our current exhibition, Still & Art. You can read the first post here.

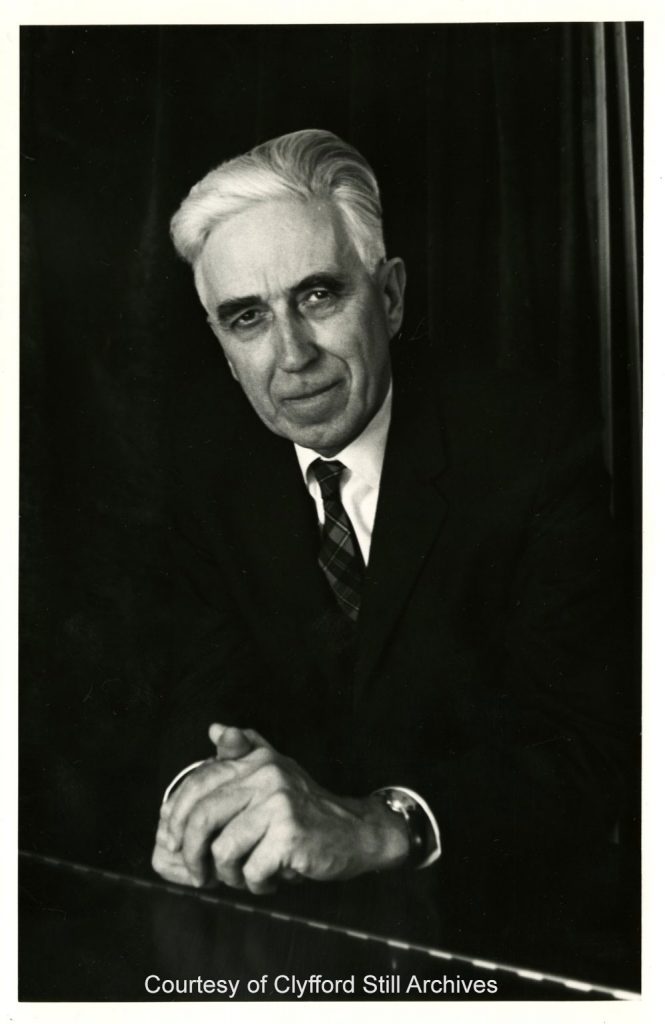

Clyfford Still, like many great artists (Jackson Pollock, Pablo Picasso, and Georgia O’Keeffe among them), was inspired by music. In an interview with art critic Thomas Albright in 1978, he said that he sought “the vastness and depth of a Beethoven sonata” in his paintings. [1] While Beethoven was perhaps Still’s biggest musical inspiration, he was not the only one. Among Still’s eclectic collection of record albums (which we are fortunate enough to have in our archives) are jazz, spiritual, folk, and even Native American recordings, in addition to the more traditional Beethoven, Bach, Brahms, and Mozart that you might expect. Looking through Still’s record collection and other archival materials, it becomes clear that despite being the son of a struggling homesteader on the rural, barren plains of Alberta, Canada, music and culture were anything but scarce commodities during Still’s youth. And they had a measurable impact on his art. Music, in particular, contributed to Still’s quest for a transcendent freedom in his work.

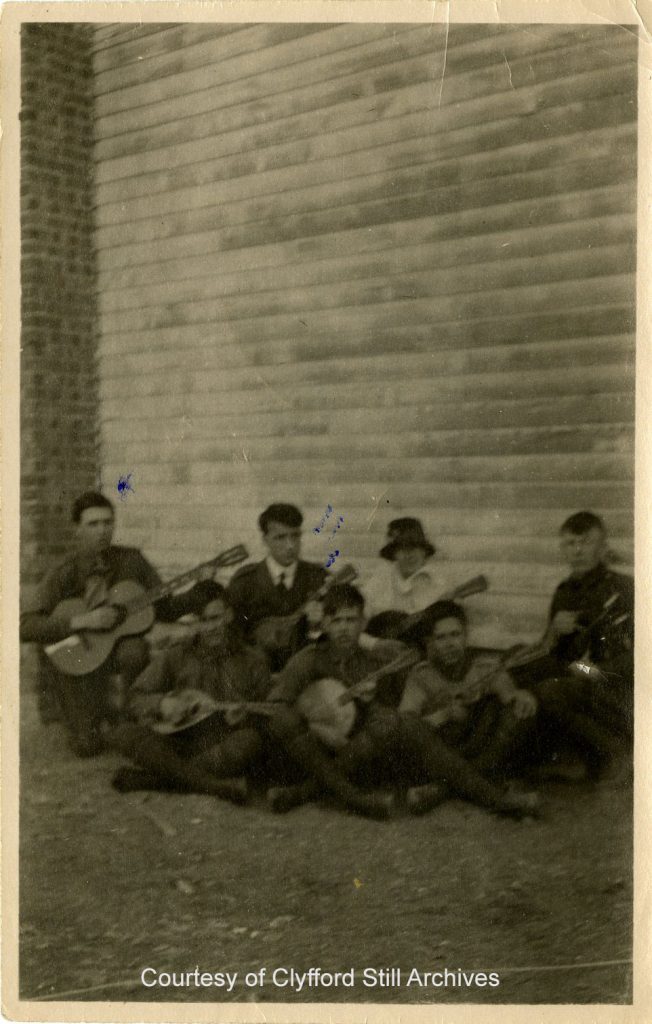

During the early 1900s, when Still (b. 1904) was a young child, his family moved back and forth between Spokane, Washington and a homestead farm in Bow Island, Alberta, Canada. But in 1914 the Stills established a residence in Bow Island, settling in and making it a more permanent home for a time. Clyfford was enrolled in Bow Island Public School and joined organizations like the Boy Scouts and his school’s mandolin trio. And while information about this period in Still’s life is relatively scarce, we do know there was a family piano at the home in Bow Island. It was on that very piano that Still learned to “play music by Chopin, Beethoven, and Schubert.” Still also played in his Boy Scout Orchestra and recalled later in life that he was at one point “undecided about whether to become a painter or pianist.” [2]

There are many accounts of Still’s childhood being one of isolation and severity, both in terms of the landscape and his family life. However, there is evidence to suggest that despite sterile farming conditions that forced most homesteaders to abandon their farms, Bow Island’s cultural life was fertile ground for a young, aspiring artist, and the community was a social one. Alfred Millar, a Bow Island homesteader whose extended family were neighbors of the Stills, described life in Bow Island as richly musical despite its remoteness. According to Millar, “You must not think all the homesteaders who lived in this new community were crude and uncultured. Many of these people were well educated and cultured in arts, music and drama.” And they got together often to play music and converse. In this context, it seems fitting that music was very much a part of Still’s development. [3]

Still’s musical youth had a lasting impact on his art, but the influence is more complex than simple admiration or emulation. Albright believed that Beethoven and others—Turner, Blake, Rembrandt—were heroes to Still because they “had liberated themselves from the particulars of time and place to achieve, in their work, a transcendent freedom.” [4] Still once said, “I want to be in total command of the colors, as in an orchestra. They are voices.” [5] He also said, “By 1941, space and figure in my canvases had been resolved into a total psychic entity, freeing me from the limitations of each, yet fusing into an instrument bounded only by the limits of energy and intuition. My feeling of freedom was now absolute and infinitely exhilarating.” [6] Through abstraction, Still achieved what he admired in his heroes: transcendent freedom. He looked to Beethoven and other influencers as guides on his path to creating something larger than the artist, something that like music is beyond words, because to Still words were burdened with meaning. Music, however, like Still’s paintings, transcended words.

Sources:

[1] Albright, Thomas. “Clyfford Still: ‘Seeking the Vastness and Depth of a Beethoven Sonata or a Sophocles Drama.’” Artnews 79 (September 1980): 159-60.

[2] Patricia Failing. “Clyfford Still: An Annotated Biographical Chronology 1904-1941,” p. 2-4.

[3] Ibid. p. 3-4

[4] Albright, Thomas. “Clyfford Still: ‘Seeking the Vastness and Depth of a Beethoven Sonata or a Sophocles Drama.’” Artnews 79 (September 1980): 159-60.

[5] Freeman, Betty. “Clyfford Still: A Study, 1968” Unpublished manuscript. Courtesy of Clyfford Still Archives.

[6] Sharpless, Ti-Grace A. “Freedom…Absolute and Infinitely Exhilarating.” Artnews 62 (November 1963): 36-39, 60.